Omega-3 and healthy aging

Some of the central mechanisms in aging include inflammation, reactive oxygen species and reduced mitochondrial function [1].

Mitochondria provide the energy that allows us to move, think, keep warm; everything activity from the triggering of a nerve impulse to running a marathon. Every cell contains mitochondria (apart from red blood cells), and mitochondria have their own DNA passed down by the mother. The number of mitochondria follow the energy needs of the cell and therefore exercise leads to expansion of the mitochondrial pool providing more energy and more strength.

The down-side of mitochondria are that they are the primary source of reactive oxygen species. This is not usually a problem but in certain conditions the balance of oxidants and anti-oxidants can cause trouble. During aging, the number of mitochondria are reduced and this is associated with mitochondrial stress, increased oxidative stress and ultimately inflammation. Inflammation can lead to more mitochondrial stress and a vicious circle can ensue.

Mitochondria are also essential for lipid metabolism and aging and obesity can both lead to dysfunctional mitochondria.

A publication by Xiong 2024 [2] shows that EPA supplementation in a mouse model has broad anti-aging effects. The work reported by this one paper is vast. In brief, the authors used different mouse models including a normal mouse left to age (24 months seems to be the retirement age for a mouse).

The paper reports how aging results in poor fur and skin, increased body weight, and dysfunction in the lungs, heart, kidneys and brain. Inflammatory biomarkers increased with age and energy production was reduced. Organ levels of omega-3 reduced with age.

Following a diet withhigh concentrate EPA, improvements were seen in almost all parameters measured, with an associated increase in organ EPA (but not necessarily plasma) and an improved omega-6: omega-3 ratio.

Amongst other things the paper describes supplementation leading to improvements in liver function and blood lipids, reduced neurodegenerative protein (tau) accumulation in the brain, reduction in cardiac hypertrophy, and increases in lipid metabolising genes.

The authors provide evidence that PPARa is the signalling mechanism by which EPA elicits these myriad effects, however, they did not perform a study where PPARa was blocked either by genetic manipulation or other inhibitory action. This is essential to show that PPAR is actually responsible for these effects.

The study provides a huge amount of data supporting a scenario that closely links dysfunctional lipid metabolism with chronic inflammation and aging and promotes EPA as a nutrient that reprograms lipid metabolism, reduces inflammation and ultimately slows the aging process.

The full paper can be read here.

TARGETING ADIPOSE TISSUE: EPAX OMEGA 3-9-11

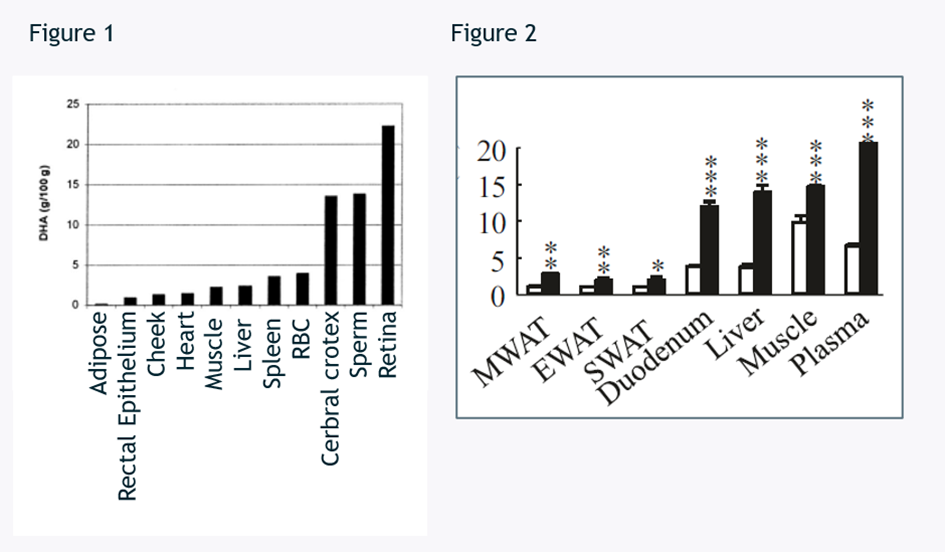

One of the main interests with EPAX Omega 3-9-11 is the effects of mono-unsaturated fatty acids on adipose tissue – one of the few areas where omega-3 doesn’t seem to reach.

In mice and humans, omega-3 shows poor accumulation in adipose tissue. This makes the accumulation of omega 9-11 to adipose tissue an interesting add-on to the long list of health benefits for omega-3.

Figure 1: DHA g / 100g of total fatty acids from human [3]

Figure 2: Omega-3 content as a % of total fat from mice. MWAT = Mesenteric white adipose tissue, EWAT = Epididymal white adipose tissue. SWAT = subcutaneous white adipose tissue [4].

Despite the above data, it should be noted that studies show omega-3 effects in adipocytes [5] and the picture of biodistribution is therefore not totally black and white.

A recent Nature communications article describes how metabolic health is a result of the liver-adipose-immune axis. Using their ex vivo system the article describes how adipose related inflammation drives insulin insensitivity in the liver [6].

This cross-talk between the liver and adipose tissue is described by others [7]. A paper from Duwaerts 2019 is well written and well worth reading and describes how obesity causes a chaotic disruption in liver and adipocyte function.

The paper describes how following a meal, excess carbohydrates are converted to fat in the liver and adipose tissue in a process called de novo lipogenesis. Insulin acts on adipocytes to take up glucose (important as a precursor in de novo lipogenesis) and additionally to increase uptake of fats from the blood.

During obesity, adipose tissue can become dysfunctional and incur insulin resistance. The lack of insulin signal can lead to the adipose tissue being fooled into thinking the body is fasting and pumps fatty acids into the blood. Additionally, adipose-insulin resistance prevents uptake of fatty acids by adipose tissue. This can ultimately lead to re-routing of fat to ectopic fat layers – for example the liver and heart etc.

This describes an intricate cross-talk between dietary status, liver, white adipose tissue and insulin levels. This complex picture opens an opportunity for multi-component products that can hit several of these key metabolic regulatory points with the potential of providing a more comprehensive metabolic effect. EPAX Omega 3-9-11 is a lipid mix selected to hit differing molecular and anatomical targets.

We have described this hypothesis in more detail in our recent publication in Teknoscienze.

1. Asejeje , F.O., Ogunro. O.B., Deciphering the mechanisms, biochemistry, physiology, and social habits in the process of aging Archives of Gerentology and Geriatrics Plus, 2024. 100003: p. 1-27.

2. Xiong, Y., et al., Omega-3 PUFAs slow organ aging through promoting energy metabolism. Pharmacol Res, 2024. 208: p. 107384.

3. Arterburn, L.M., E.B. Hall, and H. Oken, Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr, 2006. 83(6 Suppl): p. 1467s-1476s.

4. Yang, Z.H., et al., Long-term dietary supplementation with saury oil attenuates metabolic abnormalities in mice fed a high-fat diet: combined beneficial effect of omega-3 fatty acids and long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids. Lipids Health Dis, 2015. 14: p. 155.

5. Albracht-Schulte, K., et al., Omega-3 fatty acids in obesity and metabolic syndrome: a mechanistic update. J Nutr Biochem, 2018. 58: p. 1-16.

6. Qi, L., et al., Adipocyte inflammation is the primary driver of hepatic insulin resistance in a human iPSC-based microphysiological system. Nat Commun, 2024. 15(1): p. 7991.

7. Duwaerts, C.C. and J.J. Maher, Macronutrients and the Adipose-Liver Axis in Obesity and Fatty Liver. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019. 7(4): p. 749-761.

Tecknoscienze: https://digital.h5mag.com/agro...